Introduction to the Jememôtre Concept

The jememôtre represents a fascinating intersection of measurement science and human expression that emerged during France’s transformative period. This innovative concept combined practical measurement needs with philosophical ideas about individual perception and standardization across society. People needed reliable ways to communicate distances and quantities as commerce expanded throughout European regions during this era. The jememôtre addressed these challenges while reflecting broader cultural shifts toward rationalization and scientific thinking in French society. Moreover, this measurement approach demonstrated how technical innovations often mirror deeper social and intellectual movements within civilizations.

Historical Context of Measurement in France

Before revolutionary changes swept through France, measurement systems varied wildly between different regions and even neighboring towns. Merchants struggled to conduct business when every locality used different units for length, weight, and volume measurements. Consequently, trade became unnecessarily complicated, leading to disputes, confusion, and significant economic inefficiencies throughout the kingdom. Furthermore, this chaotic situation created opportunities for deception as unscrupulous traders exploited the confusion to cheat customers. The ancien régime maintained hundreds of different measurement standards, which severely hampered national commerce and industrial development. Revolutionary thinkers recognized that standardization would promote fairness, transparency, and economic growth across all French territories.

The Birth of Revolutionary Measurement Ideas

Enlightenment philosophers championed reason, science, and universal principles that could apply equally to all human beings. These intellectual currents naturally extended to practical matters like measurement, where arbitrary local customs seemed outdated. Scientists and mathematicians began proposing rational systems based on natural constants rather than historical accidents or royal decrees. Additionally, they argued that measurement should reflect observable reality and mathematical principles rather than feudal traditions. The revolutionary government embraced these ideas enthusiastically, seeing measurement reform as both practical necessity and symbolic statement. Thus, the stage was set for radical innovations in how French society would quantify the world.

Understanding the Philosophical Foundations

The concept behind this measurement approach incorporated ideas about individual experience alongside objective scientific standards. Philosophers debated whether measurement should purely reflect external reality or somehow account for human perception and experience. Interestingly, some thinkers proposed that effective measurement systems must acknowledge both universal constants and individual perspectives. This philosophical tension produced creative solutions that attempted to bridge objective science with subjective human experience. The result was a measurement framework that honored both mathematical precision and the human element in observation. Revolutionary France thus became a laboratory for testing new ideas about how societies should standardize their practices.

Technical Specifications and Design

The practical implementation required careful attention to precision, reproducibility, and ease of use for ordinary citizens. Designers created physical instruments that embodied the theoretical principles while remaining accessible to people without advanced education. These tools featured clear markings, logical subdivisions, and references to natural phenomena that anyone could observe and verify. Meanwhile, craftsmen worked to produce instruments with sufficient accuracy to serve scientific purposes while remaining affordable for commerce. The balance between precision and practicality represented a significant challenge that required innovative manufacturing techniques and quality control. Ultimately, the design succeeded in creating tools that served both elite scientists and common merchants effectively.

Manufacturing and Distribution Challenges

Producing standardized instruments across an entire nation presented enormous logistical difficulties during this turbulent historical period. Workshops needed specifications, training, materials, and quality assurance systems to ensure consistency across thousands of individual instruments. Furthermore, the revolutionary government had to establish distribution networks that could reach remote rural areas with limited infrastructure. Resistance from traditional craftsmen who preferred established methods added another layer of complexity to the implementation process. Nevertheless, reformers persisted, recognizing that successful standardization required widespread availability of accurate, affordable measurement tools. Through determination and systematic planning, they gradually overcame these obstacles and established functioning production and distribution systems.

Impact on Scientific Development

Standardized measurement revolutionized scientific research by enabling researchers to compare results, replicate experiments, and build cumulative knowledge. Scientists could now communicate findings with precision and confidence that colleagues elsewhere would understand their measurements correctly. This breakthrough accelerated progress across physics, chemistry, astronomy, and numerous other fields that depended on quantitative analysis. Moreover, international collaboration became far more feasible when researchers shared common measurement languages and standards. The scientific revolution that followed owed much to these seemingly mundane but actually transformative changes in measurement practice. French contributions to science expanded dramatically once researchers possessed reliable, standardized tools for quantifying natural phenomena.

Commercial and Economic Implications

Trade flourished when merchants no longer needed to navigate countless local measurement systems with their confusing variations. Buyers gained confidence that they received fair value, while sellers benefited from expanded markets and simplified transactions. Consequently, economic growth accelerated as transaction costs decreased and market efficiency improved throughout French territories and beyond. The standardization also facilitated industrial production by enabling manufacturers to specify parts with precision and coordinate complex operations. Additionally, taxation became more rational and equitable when authorities could reliably measure property, production, and commercial activity. These economic benefits demonstrated that measurement reform delivered practical advantages extending far beyond abstract scientific principles.

Social and Cultural Dimensions

Measurement standardization represented more than technical change; it embodied revolutionary ideals of equality, rationality, and universal human dignity. Every citizen would use the same units, eliminating aristocratic privileges and regional inequalities embedded in traditional systems. Furthermore, rational measurement reflected Enlightenment values that human reason could improve society through systematic application of scientific principles. The reform thus carried symbolic weight that resonated with broader revolutionary aspirations to create a more just society. People debated these changes passionately, recognizing that measurement systems reflected deeper assumptions about authority, tradition, and progress. Cultural transformation accompanied technical innovation as French society reimagined its relationship with measurement and standardization.

Educational Initiatives and Public Adoption

Teaching new measurement concepts to a largely illiterate population required creative approaches that went beyond traditional classroom instruction. Reformers organized public demonstrations, distributed illustrated pamphlets, and trained teachers who could explain the system clearly. Markets became educational spaces where officials helped merchants and customers understand how to use the new standards. Additionally, schools incorporated measurement education into curricula, ensuring that young people would grow up fluent in rationalized systems. Despite initial resistance and confusion, gradual familiarization helped the population adapt to the unfamiliar concepts and practices. Patient, persistent educational efforts ultimately proved essential for successful implementation of the revolutionary measurement reforms across French society.

Regional Variations and Adaptation

Different regions adapted the standardized system to their particular needs, creating interesting local variations on the universal theme. Rural agricultural communities emphasized measurements relevant to farming, while urban commercial centers focused on units for trade goods. Coastal areas naturally prioritized maritime measurements, whereas mountain regions developed specialized approaches for surveying challenging terrain. These adaptations demonstrated that standardization could accommodate local requirements without sacrificing interoperability between different areas. Furthermore, regional variations revealed how abstract universal principles must always negotiate with concrete particular circumstances and traditions. The balance between uniformity and flexibility remained a constant challenge throughout the implementation process across diverse territories.

Resistance and Controversy

Not everyone welcomed the new measurement system; many people clung stubbornly to familiar traditional methods despite official mandates. Elderly citizens found learning new concepts particularly difficult after decades of using established units and practices. Some regions resisted change, viewing measurement reform as yet another imposition from distant revolutionary authorities in Paris. Moreover, practical difficulties in transitioning from old to new systems created genuine hardships for businesses and individuals. Critics argued that reformers prioritized abstract principles over practical considerations and the difficulties ordinary people faced. These tensions generated ongoing debates about the pace of change, proper implementation methods, and appropriate balance between innovation and tradition.

International Influence and Adoption

French measurement innovations inspired reformers in other nations who recognized the advantages of rational, standardized systems. Scientists across Europe and beyond began advocating for similar approaches in their own countries, citing French successes. International scientific organizations promoted standardization as essential for advancing knowledge and facilitating collaboration across national boundaries. Gradually, the French model influenced measurement practices worldwide, though adoption occurred unevenly across different nations and regions. Some countries embraced the new approach enthusiastically, while others maintained traditional systems for decades or even centuries. Nevertheless, the French example demonstrated that measurement standardization was possible and beneficial, encouraging global movement toward common standards.

Technical Improvements and Refinements

Early implementations revealed problems that required corrections, modifications, and ongoing refinement through successive iterations and improvements. Scientists discovered measurement errors, manufacturing inconsistencies, and design flaws that needed addressing to achieve the desired precision. Consequently, subsequent versions incorporated improvements based on practical experience, user feedback, and advancing scientific understanding of measurement principles. Craftsmen developed better production techniques that increased accuracy while reducing costs, making instruments more accessible to average citizens. Additionally, theoretical work refined the underlying mathematical foundations, ensuring the system rested on the most solid possible basis. This iterative improvement process demonstrated that successful innovation requires continuous learning and adaptation rather than assuming perfection initially.

Legacy in Modern Measurement Systems

Contemporary measurement practices throughout much of the world descend directly from these revolutionary French innovations and standardization efforts. The metric system that dominates international science and commerce traces its origins to the measurement reforms of this era. Modern people often take for granted the standardization that enables global trade, scientific collaboration, and countless everyday activities. However, this convenient uniformity required visionary thinking, determined implementation, and gradual acceptance across decades of social transformation. The legacy demonstrates how technical innovations can reshape society when they align with broader cultural movements and values. Today’s interconnected world would be impossible without the standardization pioneered during France’s revolutionary period and subsequently adopted globally.

Philosophical Debates About Measurement

Deeper questions about the nature of measurement, perception, and reality continued to engage philosophers and scientists alike. Thinkers asked whether measurement reveals objective truth or merely represents convenient human conventions for describing experiences. Some argued that all measurement involves subjective elements because human observers inevitably influence what they measure and record. Others maintained that proper scientific measurement transcends individual perception to capture genuine features of external reality. These philosophical debates enriched understanding even when they didn’t resolve fundamental questions about the relationship between measurement and truth. Furthermore, such discussions highlighted how seemingly technical matters connect to profound issues about knowledge, reality, and human understanding.

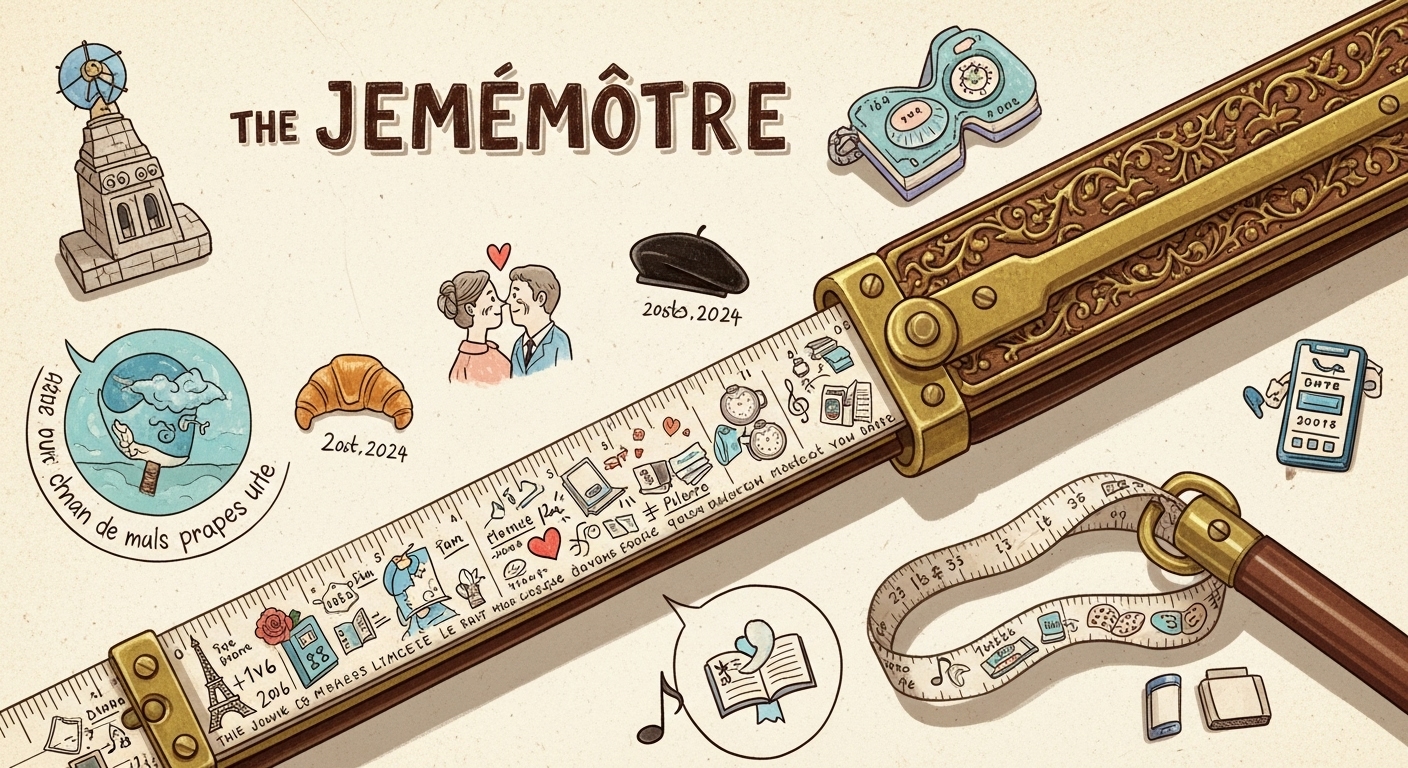

Artistic and Literary Representations

Writers, poets, and visual artists explored measurement themes in creative works that reflected broader cultural fascination with standardization. Some celebrated rational measurement as emblematic of progress, enlightenment, and human mastery over chaotic natural forces. Others expressed nostalgia for traditional methods or anxiety about reducing human experience to numerical quantities and standardized units. Artists created allegorical representations showing measurement as both liberating and constraining, depending on perspective and particular social circumstances. These creative responses demonstrated that measurement reform resonated far beyond narrow technical or commercial concerns among specialists. Cultural production reflected and shaped public attitudes toward standardization, contributing to ongoing social negotiations about appropriate balance between uniformity and diversity.

Practical Applications in Daily Life

Ordinary people encountered the new measurement approach in markets, workshops, farms, and homes throughout their daily routines. Buying fabric, selling produce, building structures, and cooking meals all required measuring quantities using the standardized units. Initially, many found the transition confusing and frustrating, preferring familiar methods they had used since childhood. However, practical advantages gradually became apparent as commerce simplified and disputes over measurements decreased noticeably across communities. Children who learned the new system from the beginning adapted most easily, eventually teaching their own children. Thus, generational turnover facilitated acceptance as older populations gradually gave way to younger cohorts raised with standardization. Daily practice ultimately proved more important than abstract arguments for winning popular acceptance of the innovations.

Comparison With Other Measurement Traditions

Different civilizations developed their own measurement systems reflecting particular cultural priorities, available technologies, and historical circumstances. Ancient societies based measurements on human body parts, creating systems that felt natural but varied between populations. Asian traditions developed sophisticated measurement approaches that differed significantly from European methods in underlying principles and practical applications. Islamic scholars made important contributions to measurement science that influenced later European developments, including the French innovations. Comparing these various traditions reveals both universal human needs and diverse cultural solutions to common practical problems. Understanding this diversity enriches appreciation for the particular choices French reformers made when designing their standardized system. No single approach represents the only possible or necessarily superior solution to measurement challenges societies face.

Gender and Measurement Practices

Women’s relationship to measurement involved particular patterns shaped by traditional gender roles and economic participation in society. Female merchants in markets needed measurement literacy to conduct business, while domestic activities like sewing required precise measurements. However, formal measurement education often excluded women, limiting their access to technical knowledge and specialized measurement instruments. Revolutionary rhetoric about universal equality sometimes extended to measurement access, though practice lagged behind theory in many cases. Women’s measurement practices in domestic and commercial spheres influenced how standardization actually functioned in everyday life. Gender analysis reveals that measurement reform affected different population segments unequally, with implications for economic opportunity and social participation.

Connection to Political Authority

Measurement standardization represented an assertion of central authority over regions that had previously maintained significant practical autonomy. Local elites sometimes resisted measurement reforms as threats to their power and traditional prerogatives within their territories. Revolutionary authorities recognized that successful standardization would strengthen centralized control and weaken regional power bases throughout France. Consequently, measurement reform became entangled with larger political struggles over the proper distribution of authority in society. Citizens understood that accepting new measurements meant acknowledging revolutionary government legitimacy and its right to regulate daily life. Political dimensions transformed technical measurement questions into contests over sovereignty, legitimacy, and the proper relationship between citizens and state.

Religious and Moral Dimensions

Religious authorities sometimes viewed measurement reform as part of broader secularization that challenged traditional church authority and values. Traditional measurements often had religious origins or associations that gave them sacred character in popular consciousness and practice. Replacing these with rationalized secular alternatives could seem like an attack on religion itself to devout believers. However, some religious figures supported measurement reform as consistent with God’s rational ordering of creation and natural law. These debates revealed tensions between religious tradition and secular rationality that characterized revolutionary period conflicts more broadly. Moral arguments about honesty, fairness, and justice in commerce connected measurement practices to ethical concerns with religious dimensions. Thus, measurement reform engaged profound questions about the proper sources of authority and moral guidance in society.

Environmental and Agricultural Context

Agricultural measurements required special attention since farming represented the economic foundation supporting most of the French population. Land area, grain volumes, livestock weights, and crop yields all demanded accurate measurement for taxation and commerce. Rural populations needed practical tools appropriate for field conditions rather than laboratory precision instruments designed for scientific research. Seasonal variations, weather conditions, and diverse soil types complicated agricultural measurements in ways urban commercial applications didn’t face. Reformers had to ensure their standardized system accommodated these agricultural realities while maintaining consistency with broader measurement principles. Successful implementation in rural areas proved essential for legitimizing the reforms and demonstrating their practical value beyond cities. Agricultural adaptation thus represented a critical test of whether standardization could truly serve all French citizens effectively.

Future Trajectories and Ongoing Evolution

Measurement systems continue evolving as new technologies enable unprecedented precision and new scientific fields require novel measurement approaches. Digital technologies have transformed how people create, store, communicate, and utilize measurements in countless applications worldwide today. Quantum physics requires measurement concepts that challenge common sense intuitions developed through everyday experience with ordinary objects. International organizations continue working toward global standardization while accommodating legitimate needs for diversity in specific contexts and applications. The revolutionary French innovations represented one stage in an ongoing human project to develop ever more sophisticated measurement capabilities. Future generations will undoubtedly develop approaches that seem as revolutionary to them as French reforms seemed to eighteenth-century observers. Understanding this historical perspective helps us appreciate both continuity and change in humanity’s long engagement with measurement.

Conclusion: Measuring Human Progress

The measurement innovations that emerged from revolutionary France transformed not just technical practices but human understanding of progress itself. Standardization demonstrated that human reason could rationally reorganize society to serve justice, efficiency, and shared prosperity more effectively. These reforms showed how seemingly mundane technical changes can embody profound philosophical principles and reshape entire civilizations. The legacy continues influencing contemporary life in countless ways, from international commerce to scientific research to everyday activities. Understanding this history enriches appreciation for how human societies develop, implement, and adapt to transformative innovations over time. Measurement standardization ultimately represents humanity’s ongoing effort to create shared frameworks enabling cooperation, understanding, and collective advancement across differences.